EDITOR’S NOTE: One week ago, 17 people age 14 – 49 were killed in a shooting at a high school in Parkland, Florida. Today, high school students across the country are planning walkouts over the next month to protest gun laws across the nation. Most have probably never heard of the East L.A. 13 or the Chicano student walkouts of 1968.

50 years ago, a group of students in East L.A. led a series of walkouts that resulted in change to the education system that many thought was impossible. This was before social media. Before 24-hour news cycles. Before cell phone videos. The 1968 Walkouts changed the lives of thousands, if not millions, of students. We are proud to help tell their story on the 50th anniversary of the walkouts, as a new generation of students takes up their banner to use walkouts as a megaphone for their voices to be heard.

THE BIRTH OF THE CHICANO STUDENT MOVEMENT

It was the height of civil rights activism. Spring of 1968.

Five years prior, Martin Luther King, Jr., inspired a nation with his I Have A Dream speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial following the March on Washington. Not long after, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law. A year later in the Spring of 1965, more than 600 protesters marched from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. A few months after that, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 would be signed into law.1

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles County, the largest Latino community in the United States had more than 130,000 students attending area schools.2 And their prospects were dim. Graduation rates were one of the lowest in the country. The dropout rate at Garfield High School in East Los Angeles was a staggering 57.5%. Average class sizes in area schools were 40 students and the ratio of school counselors to students was one counselor to 4000 students.3

Mexican-American students went on to have a college graduation rate of ~0.1%, often due to lack of access to college-readiness courses and lack of support from teachers and administrators who encouraged the students to not even try for college.4

Put simply, the students were being held down.

THE SPARK OF INSPIRATION

But a spark was lit in 1963. Sal Castro — a teacher at Lincoln High School in East Los Angeles, a Mexican-American, and an educator who worked to instill pride in his students’ Chicano heritage — led the first Chicano Youth Leadership Conference at Camp Hess in Malibu. This conference would inspire and motivate a generation of leaders, including future Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, California Supreme Court Associate Justice Carlos Moreno, and filmmaker Moctesuma Esparza.5

But, first, it would be the catalyst for the 1968 walkouts.

Moctesuma Esparza — who first attended the Chicano Youth Leadership Conference in 1965, would be one of the primary organizers of the walkouts, and later produced an HBO film about the events — described the cultural climate during an interview with democracynow.org during the 2006 release of the Walkout film:

“This is 1967, while the Vietnam War is in full bore, and protests are growing, and the Civil Rights Movement is flourishing. And throughout the world, young people are looking to change the world. And this was not lost on the kids in East L.A. They were able to see what their own circumstances were and how they were being oppressed, how they were being denied an opportunity for an education, an opportunity to fulfill their lives. And so, it was not difficult to organize them.”6

From that political and social climate, this small collection of young college and high school students would come together under the leadership of their teacher, Sal Castro, to organize a series of walkouts elevating the needs of their community.

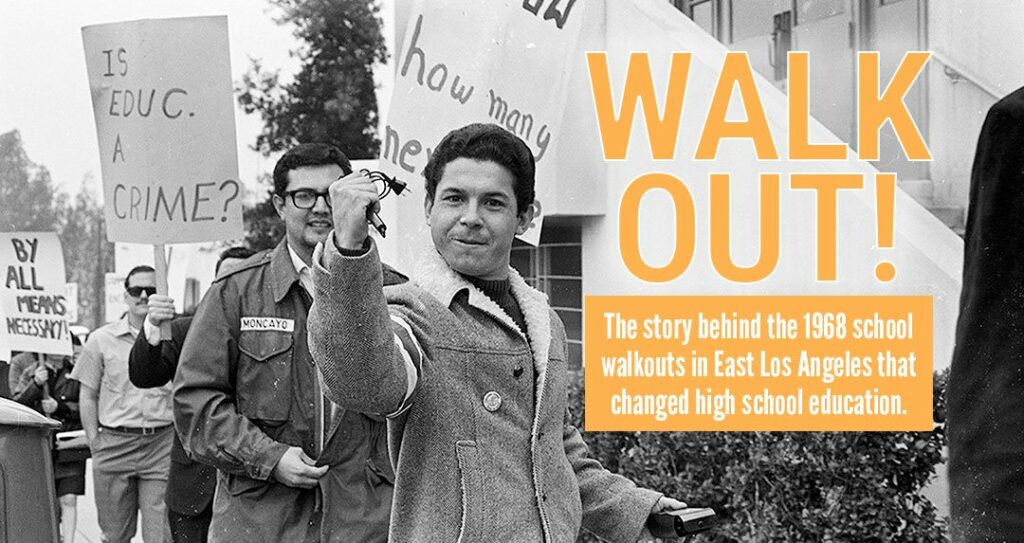

THE WALKOUTS OF 1968

It took six months of planning. The walkouts were coordinated to take place on March 6, 1968, at 10 a.m.7

An event invite couldn’t be created on Facebook. A viral video couldn’t be uploaded to YouTube. A message couldn’t be spread on Twitter. The students had to organize one-on-one. They had to plan after school and on the weekends. In between homework and jobs.

They built up support amongst East L.A. schools and the student bodies were ready. Maybe too ready. Because on Friday, March 1, students at Wilson High School walked out five days early in an impromptu protest of the cancellation of a student-produced play.8

But this didn’t stop the coordinated effort from coming together again on the planned March 6 walkouts. And again and again over the ensuing week. All told, an estimated 15,000 students walked out of classes from Woodrow Wilson, Garfield, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Belmont, Venice and Jefferson High Schools.9

They walked out despite school administrators barring doors. They walked out despite helmeted police officers wielding night sticks. At the time, there were two reported cases of student beatings during the March 6 walkout at Roosevelt.10

And, yet the violence was so much more extreme. Despite news outlets like CBS, NBC, and the L.A. Times being at the walkouts, the police violence toward the students was not covered in the media. Esparza recalled the violence during his interview with democracynow.org:

“These were high school kids who were peacefully protesting for their rights. They were children. And they were brutalized. There are blows that were recorded on film that were like death blows. It was really, really awful. And when that footage was finally discovered in 1995, when the research was being done for the PBS documentary Chicano, it was astonishing to us that that footage had survived and even existed.”

Luis Garza, a photojournalist for La Raza at the time of the walkouts, saw firsthand what the students faced.

“You’re going up against an authoritative system that allowed for no protests and would rather suppress it rather than engage in dialogue,” he said. “So there were consequences.”

“You have the LAPD. You have sheriffs. You have undercover surveillance. You have intimidation and threats that are being made,” he continued. “You’re being castigated and vilified for protesting for a subject that does not take into account who you are what you’re trying to express.”

The violence might have escaped popular attention, but the message of the students did not. Carrying signs, and many joined by family members, students brought greater light to the racism and marginalization happening in their schools. Their walkouts and message started to finally catch the attention of the school board.

But it took time.

“They were not concentrated into a day or a week,” recalled Garza. “The evolution of those walkouts was a slow and steady process. People got arrested. People got indicted. People had to go to court. People spent jail time.”

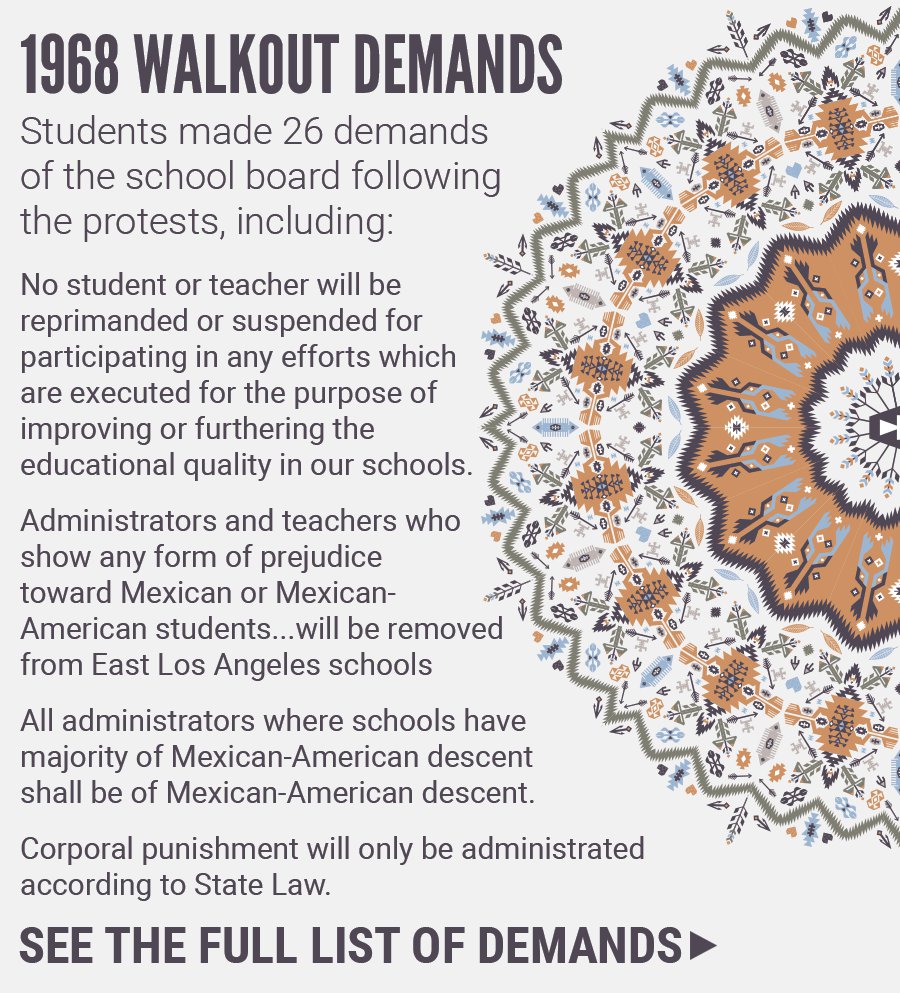

THE STUDENTS MAKE THEIR DEMANDS

On March 28, 1968, more than 1,200 community members came together in front of the Los Angeles Board of Education to support the students as they presented their demands.

But the Board denied their demands.

Three days later, 13 of the walkout organizers — later known as the East L.A. 13 — were arrested for “conspiracy to disturb the peace.” Protests took place outside the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles calling for their release. It wasn’t long before 12 of the 13 were released.

Sal Castro, the teacher who had inspired so many students to take pride in their heritage, remained held for much longer and later lost his teaching position at Lincoln High School. But thanks to round-the-clock sit-ins at the L.A. School Board office, Castro was given back his job and began teaching again.11

While policies and schools didn’t change at first, the students and community leaders never stopped advocating for change. Despite the arrests. Despite the initial denial of demands.

And, over time, things began to change.

Los Angeles schools started to see more Mexican-American administrators, more bilingual educators, and, eventually, superintendents. The 1970s saw significant increases in the number of Latinos attending colleges and universities across the nation.12

But it would take 40 years for students in Los Angeles to gain their rights to college-readiness programs through district policies. This part of the Walkout story takes us to Part 2: Finally Answered.

Read Part 2 of the Walkout Series at 40 Years After “The Walkout” — A Turning Point in LAUSD Education Reform.

And we invite you to donate to United Way of Greater Los Angeles and support programs like our Young Civic Leaders Program that help empower students to become leaders in our local communities.

1. http://www.history.com/topics/civil-rights-movement-timeline

2. http://www.pbs.org/video/latino-americans-los-angeles-walk-out/

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_L.A._walkouts#Background

4. http://www.pbs.org/video/latino-americans-los-angeles-walk-out/

5. http://newsroom.ucla.edu/releases/Sal-Castro-and-Chicano-Youth-Leadership-7077

6. https://www.democracynow.org/2006/3/29/walkout_the_true_story_of_the

7. http://www.pbs.org/video/latino-americans-los-angeles-walk-out/

8. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/East_L.A._walkouts#Walkouts

9. https://www.kcet.org/shows/departures/east-la-blowouts-walking-out-for-justice-in-the-classrooms

10. https://www.kcet.org/shows/departures/east-la-blowouts-walking-out-for-justice-in-the-classrooms

11. https://eastlablowouts.weebly.com/timeline.html

12. http://www.pbs.org/video/latino-americans-los-angeles-walk-out/